By Phyllis Sigal

Wheeling, W.Va. -(November 9, 2022)–It was in the wee hours of a spring morning in 1993 when the iconic Sweeney punch bowl was moved to its new home. This stealth move was made to avoid the attention of onlookers as the behemoth glass piece was relocated a few hundred yards from Oglebay Institute’s Mansion Museum to the sparkling new glass museum in the lower level of the Carriage House Glass Shop.

The punch bowl has been firmly entrenched in its case since then — so entrenched that it was the only collectible that was not packed up during the recent revamping of Oglebay Institute’s Glass Museum.

The museum’s long-awaited reopening took place November 7 — shuttered since Feb. 1 when a sprinkler line burst a floor above the home of the Institute’s glass collection, flooding display cases, seeping into ceiling tiles, saturating carpet and warping interpretive panels.

Coincidentally, another of Oglebay’s sprinkler systems struck in the museum’s history — on that early spring morning of 1993 as staff members were walking carefully across the lawn to the truck that would transport the Sweeney punch bowl to its new site. It was at that moment when the timed lawn sprinkler system began to spray, shared Dr. Frederick Lambert, who was president of Oglebay Institute at time.

“Needless to say, the bowl got a washing, but none the worse for the wet, but the staff got drenched in the process,” he said.

Renovated, Redesigned, Reimagined

The immediate task at hand last winter after the sprinkler line break drenched the museum was the painstaking job of emptying the display cases of thousands of pieces of glass, that were then washed, inventoried, wrapped and packed into boxes. That alone took staff members five months to complete. Luckily, not one piece of glass was lost or damaged — and many of the 4,000 objects in the collection are irreplaceable.

And then there was the mold problem that was uncovered during the cleanup. “The walls had to be taken down to the cement block,” said Christin Byrum, director of the Museums of Oglebay Institute.

“This is the first major update to our Glass Museum in almost 30 years,” said John Culler, chairman of the Oglebay Institute Board. “The wonderful staff of the museum has worked extremely hard to reimagine and update the way the collection is displayed. Their dedication, as curators of this amazing collection, has given our community a great space to learn about the history and heritage of an important industry.”

A ‘Real Jewel’ in the Community

“We are fortunate to have such talented professionals at the helm of our museums,” commented Michael Hires, Committee of the Museums of Oglebay Institute chair. “They leveraged a terrible accident, and, in the process, transformed the glass museum. Having a front-row seat during the process of cleaning, storing and protecting the collection, and making significant changes including new floor treatment, wall color and lighting — all of which highlight the color and details of the collection in new and different ways — to seeing the reinstallation happen in real time, has been an honor. The space feels fresh and modern, a real jewel for our community,” Hires added.

Visitors to the renovated museum will undoubtably enjoy a much-improved experience thanks to the physical and interpretive updates.

One of the most striking and important updates to the museum is the lighting, Byrum said. All the lighting is LED and measures 5,500 on the Kelvin scale. (Tiffany uses 6,500 to make their diamonds sparkle, Byrum noted.) Kara Yenkevich, curator of collections at the museums, explained that the higher Kelvin allows the true colors of the glass to shine.

Other physical improvements to the facility include all-new luxury vinyl flooring with an industrial look and feel to mimic a glass factory; soothing gray walls; black background in the display cases that make the glass objects pop; new seating throughout; and larger and more open spaces with a better flow throughout the galleries. One addition is a new gallery dedicated to changing exhibits that will “allow us to show off” more pieces in the collection, Yenkevich pointed out. She also hopes that will entice visitors to return again and again.

Product, Process, People

Interpretive improvements allow visitors to delve into the history and heritage of Wheeling’s glass-making industry. The informational panels have a new focus — the “three Ps,” Yenkevich explained. They are: Product — history of the glass companies and what they created; Process — tidbits about the chemistry of glass and how it’s made; and People — those who made the glass.

‘Previously, the glass museum focused on the glass itself,” Yenkevich said. An important new layer focuses on the labor perspective, the people — the piece that would surely please the late Robert DiBartolomeo, director of the Mansion Museum during the 1960s and a nationally known expert in Wheeling glass.

“Whenever you look at a piece of glass in your hand, remember who made it,” he used to say, noted Holly McCluskey, curator of glass at the Museums of Oglebay Institute.

No doubt, DiBartolomeo would be quite proud of the renovated, redesigned and reimagined Oglebay Institute Glass Museum that now shines the spotlight on the craftspeople who toiled for decades in the many Ohio Valley glass factories.

A mural in the elevator and one at the future dedicated entrance bring visitors face to face with life-size workers. “The additional details and reinterpretation give context to the lives of workers at the time. You even ride the elevator with workers to get to the ‘factory floor’ to see this world-class collection,” Hires said.

“Thirty-six percent of all child laborers worked in the glass industry,” Yenkevich said. The museum explores who was working in the industry and what their jobs were. “Roles were defined by gender and age,” she explained.

Yenkevich said that it takes about eight people to make one piece of pressed glass, and could take up to 30 to make a piece of blown glass.

All in a Name

Newly established with the renovations are naming rights to galleries. Funders were offered a 10-year or a lifetime of the museum naming right, Byrum explained.

The main gallery has been funded by the McWilliams Foundation. “They opted to name it the Artzberger Gallery in memory of John and Judie Artzberger,” Byrum said. Artzberger was director of the museums when the glass museum opened in 1993.

A new space, thanks to the reconfiguration of the museum, has been underwritten by Jay Frey and Michael Hires. It is called the Frey-Hires Gallery. The inaugural exhibit features glass celery vases. “My husband, Jay Frey, and I are thrilled to be part of the transformation and have made a contribution to name the Frey-Hires Gallery,” Hires said.

A third gallery, the Dr. Frederick A. and Julie L. Lambert Gallery, will highlight pieces called whimsey. “They are fun things — not standard glass pieces — pieces workers made to take home with them,” noted McCluskey. Dr. Lambert, as president of Oglebay Institute at the time of its opening, was instrumental in the creation of the facility. And his wife, Julie Lambert, helped with the installation in, Byrum said.

A fourth exhibition space displays items that are on loan courtesy of Island Mould and Machine Co. Founded in 1939 on Wheeling Island by J.D. Weishar, the company is now located in the Fulton section of Wheeling, Grandsons Thomas J. and John J. Wisher currently are president and vice-president, respectively. Island Mould made the original mould for the replica of the famed Sweeney punch bowl, created by Imperial Glass.

“A lot of glass wouldn’t exist without moulds,” Byrum said, noting that the moulds are quite relevant to Wheeling’s glass history. Several examples are on display in the gallery.

Historical Significance

“Glass manufacturing in Wheeling is an important part of our history,” Culler said. “The skilled craftsman that created the glass products really put Wheeling on the map and helped to build a national reputation for the city.”

The glass industry is a huge part of Wheeling’s history for many reasons — one of which, McCluskey explained, is the fact that so many of Wheeling’s men, women and children labored in glass factories. “We attracted a skilled labor force from Europe.” Wheeling was a “mecca,” she said.

The J.H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company — the largest glass factory in the United States in 1887 — shipped glass all over the world, to Iceland, Greenland, Persia and South America, McCluskey said. In fact, Hobbs-Brockunier invented a glass-making formula adding bicarbonate of soda to the mix for pressed glass, which is still used today. “This formula enabled Wheeling to become the Henry Ford of glass-making,” she said. The addition of the bicarbonate of soda made the glass set up in the mould clearer and better, she explained.

“Through lucky circumstances, Wheeling was one of the best places to make glass — it had everything,” McCluskey said. “Silica sand, limestone and soda ash were all easily available here.” Also, Wheeling had the Ohio River and National Road — both assets to the all-important aspect of transportation.

Coal and natural gas helped fuel the success of the industry because if its abundance in the Ohio Valley. Heat certainly was at the center of glass-making.

Yenkevich explained that the glass industry shifted from New England (where wood fueled the industry’s heat source) to the Ohio River Valley because of the natural gas and coal, as well as labor unions — and therefore higher pay — that were centered here.

A ‘World Class’ Collection

“It is important for the community to understand that this is a world-class exhibit,” Hires said.

The Institute began collecting glass in 1937 when Letitia Sweeney Ewing donated several pieces to the Mansion Museum. Ewing was the daughter of Thomas Sweeney, who, along with his brothers, founded Sweeney Glass Co. — the company that created the massive Sweeney punch bowl. The punch bowl rested atop the Greenwood Cemetery grave of Michael Sweeney (Thomas’ brother) for 74 years. When children began shooting at it with BB guns, relatives asked that the Mansion Museum take it for safekeeping. Former Oglebay Institute employee, the late Phil Maxwell, helped move the relic in 1949.

According to Lambert, “Once the Glass Museum was opened (in 1993), the museum’s reputation grew nationally, and it received recognition and commendation in national glass associations. The museum’s accrediting agency spoke in glowing terms of the collection, its display and interpretation. The glass museum also became a preferred repository for other significant glass collections, both regional and national.

“Such success is never the work of any one person but a team effort, but we would be remiss if we didn’t highlight and praise the work of Holly McCluskey in her consistent efforts to maintain consistent quality display, interpretation and programming related to the museum’s glass collection,” Lambert added.

Curator Favorites

Along with the impressive punch bowl, there are beautiful cut crystal decanters and many other specimens of Sweeney Glass. “It was very popular down South, shipped to beautiful homes there. It was very expensive,” McCluskey said.

The museum also boasts the largest collection of Northwood glass in the world as well as the largest public collection of Duval glass in the world. A Duval punch bowl — small but elegant — is one of McCluskey’s favorites in the museum’s collection. “It’s a magnificent piece,” she said. Thirteen pieces of Duval Glass, which date back to 1825 to 1837, are on display. “They’re stunning. And it’s glass — which doesn’t always survive.”

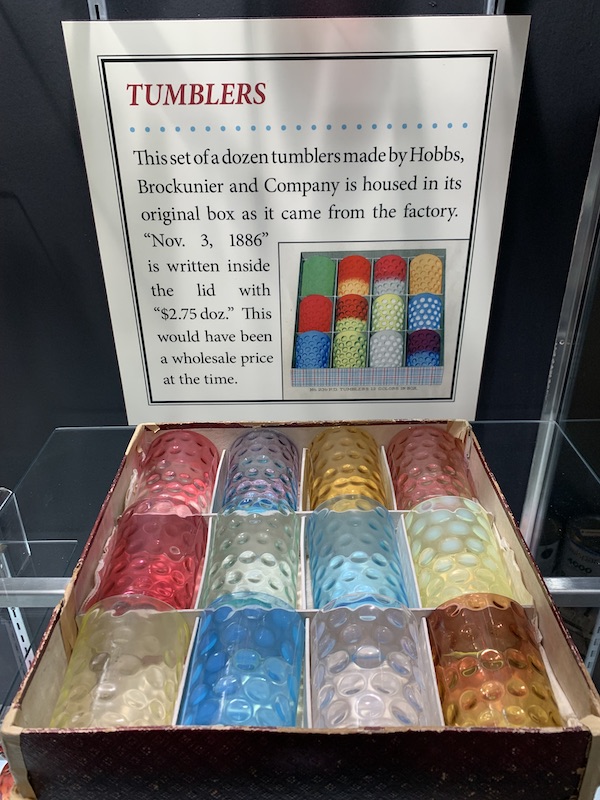

Another of McCluskey’s favorites is a set of 12 colored tumblers made by Hobbs, Brockunier and Company. Visitors can see them displayed in the original box as it came out of the factory in November of 1886. A page from the wholesale catalog accompanies the tumblers in the display case.

Pieces on display crafted by Hobbs, Brockunier and Company include both notable and everyday pieces: a glass bell made for John Bell who ran against Abraham Lincoln; a pitcher from the American Centennial; engraved pieces that were wedding gifts for a Mr. and Mrs. McNell; and a cake stand with a hand on the pedestal inspired by the Statue of Liberty.

Other don’t-miss pieces in the collection:

• Several pieces of peachblow glass, one of the most popular and most difficult types to make because of the many layers;

• A very rare Central Glass candlestick made in the image of a Wheeling Suspension Bridge sandstone tower for a bridge celebration in 1848;

• Pieces from Central Glass including ones made for the White House for President Harding in the 1920s;

• Rare Silveria pieces from the collection of Harry Northwood who came from England to start the Northwood Glass Company in Wheeling;

• The only (“that we know of,” according to McCluskey) carved cameo brooch made in America. Harry Northwood made it himself for his fiancé.

Oglebay Institute’s Glass Museum is located on the lower level of the Carriage House Glass gift shop at 1330 Oglebay Drive, Oglebay. Visit online for museum hours.