Cancer is a fact of life. We all know someone who’s fought it, and most of us know people who have both won and lost that battle. Cancer changes lives. It has a way of clearing away cobwebs and refocusing priorities. It shines a light on what’s important. To that end, in March and April, Oglebay Institute’s Stifel Fine Arts Center will present a lecture series in conjunction with the “The Art of Healing” exhibit, which will explore the role of art in the cancer patient’s journey.

One of the guest lecturers will be Renée Nicholson, a professor in the multidisciplinary studies program at West Virginia University. Though she was trained in classical ballet, Nicholson was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis at an early age. She had to make a career change, so she obtained a graduate degree in creative writing. While she was teaching, a physician who wanted to help an ALS patient write a memoir contacted her. The patient lacked the motor function to do it himself. Nicholson was intrigued by the idea, as was the medical community at WVU. After some research, they learned of a program called Narrative Medicine, in which medical teams—from doctors and nurses to therapists and rehabilitators—use a patient’s narrative, or story, to facilitate treatment and promote healing.

Narrative Medicine Clinical Trial

Nicholson and Dr. Carl Grey of WVU began a clinical trial using narrative medicine with patients in chemotherapy. It started as a way to help palliative patients develop their advance care directives. Patients often cannot speak for themselves when the time comes to make decisions; hearing and understanding their stories helps both family and medical teams understand their wishes. Nicholson and Grey also believed storytelling would help with patients’ quality of life. As a writer, Nicholson’s job was to hear and transcribe these stories.

“I would go in and sit with patients and take them through some guided prompts,” she said. “I never asked them about their disease, just about what they felt their story was.”

She worked with more than 60 patients during the two-year study. In addition to training others in the technique, she developed a course in the Honors College called “Medicine in the Arts,” for pre-med students. Nicholson believes it’s important to teach narrative medicine to future practitioners, and the study intrigued many other medical professionals at WVU.

The Art of Storytelling

Nicholson said that each patient was different and unique, not only in their diagnosis and prognosis, but also in the way they told their stories. Some were ebullient; others spoke quietly, with reserve. She took cues from the oncology nurses, who often matched their mannerisms and speaking style to the patient they were attending to. She found this helped to forge a connection with the storyteller.

What stood out to Nicholson? She said that patients often spoke about food. Chemotherapy changes the way things taste, and so it also alters the way they remember food. She heard lots of fried chicken recipes.

She also discovered that most patients spoke proudly about their life’s work.

“Our number one theme that people talked about was the work they did in their lives,” she said. “There’s so much pride and dignity in what they did.”

Nicholson said that West Virginia featured in many stories, as well.

“Most of the patients were from West Virginia,” she said. “I felt like I got the story of my state and the story of this place and this region. I got these roots stories. So many people talked about their connection to the land, their mountain, their woods, their farms. I felt like…I really understand this place where I live so much better.”

A Portrait of the Artist in Wheeling, WV

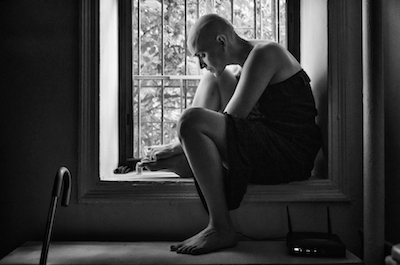

Because this was a clinical study, Nicholson couldn’t tell the patients’ stories publicly. One Wheeling woman, however, wanted to share. Lacie Wallace was a multimedia artist, a sitting model for other artists, and a mom of two. She was the 20th patient in the narrative medicine study. Right away, Nicholson knew Lacie was unique.

“She was dressed to the nines every time she came in,” Nicholson said. While most patients arrived for their infusions in comfortable clothing, Lacie wore dresses, makeup, and jewelry. She played the ukulele and worked on art projects during the times she was admitted to the hospital. Nicholson said she knew she was in the presence of an amazing artist:

“[Lacie’s] art just dropped my jaw. It was amazing and beautiful and vibrant. I knew I was looking at something pretty extraordinary.”

Lacie created interactive art and wanted people to be able to touch it in a hands-on experience.

“I knew this woman had this extraordinary talent,” Nicholson said. “Lacie wanted to see her art out there. She wanted to be known.” So Nicholson arranged for Lacie’s work to be featured at WVU’s Health Science Center Library in an exhibit she titled “Bodies of Truth: An Artist’s Creative Exploration through Cancer.”

The event meant so much to Lacie.

Seeing Firsthand the Healing Power of Art

“She was really excited, because one of the things that Lacie was worried about was that people would never get a chance to experience her art, and that she would be forgotten or never known,” Nicholson remembered. Lacie said the act of creating art made her feel better, like herself in spite of the cancer. Towards the end she was still collaging and making amazing pieces from her hospital bed. It was a lesson not only for Nicholson, but for the oncology team that worked with Lacie.

“I got to see how art can really be healing,” Nicholson said. “It has the ability to bring people together. She just had that way of connecting with people. I’m so happy we were able to have her exhibit. The students really connected with her artwork.” Others did too. The show was attended by a rich mix of people including students from many disciplines, numerous doctors and nurses, and professionals who had worked with Lacie.

Lacie passed away in 2017, but her art lives on.

“It helped us understand the journey she went through,” Nicholson said. “And I don’t know that I’ll ever have an experience quite like that in my life again. All the way until the end she was just a light. You felt it when you were in her presence. All of the patients leave something with me. They all touch me.”

The Takeaway

Columbia University’s own Narrative Medicine program states that the care of the sick unfolds in stories. Nicholson agrees. Her experience with the study taught her the power of story. She’s learned to move past her own ego.

Writers, in particular, often find themselves consumed by their work, exposing their vulnerability on the page. But after hearing the stories in the Narrative Medicine study, Nicholson has realized the depth of true vulnerability. She found it in the infusion patients and in their stories. And therein lies the irony: vulnerability and true openness come when we face tremendous loss.

“The great tragedy of life is that it ends,” she said. “It also makes it valuable.”

Cancer can strike anyone. Nicholson has faced it in her own family, as most people have. But the power of these stories helps to ease the struggle, if only for a moment. She’s glad to be a part of that healing.

“Cancer is indiscriminate,” she said. “It leaves a hole, and that’s something that anyone who’s been touched by cancer understands. I hope that having these stories can leave one little piece of connection. You can come back and read and hear your loved one’s voice again on the page. If they do that, in my book it’s all been worth it.”

–Author Laura Jackson Roberts

Learn More: Nicholson Discusses Her Work March 21

Nicholson will discuss her work with Narrative Medicine and share her experiences working with Lacie Wallace during a public program at 6:30pm Thursday, March 21 at the Stifel Fine Arts Center. The program is free and open to the public. Light refreshments will be served beginning at 6pm.

Reservations are requested for planning purposes, but are not required. Reserve online or by calling 304-242-7700.

The Art of Healing Exhibit

“The Art of Healing” exhibition explores the therapeutic power of the creative process to address the physical, emotional and spiritual needs of cancer patients and their loved ones.

Through drawing, painting, photography, sculpture and written word, artists chronicle their journeys from a variety of perspectives and offer powerful, visual portrayals of the emotional impact associated with a physical illness. The exhibition evokes a better understanding of the everyday challenges of those affected by cancer, honors the lives and memories of those fighting the disease and illustrates how art provides a sense of healing, belonging and relating in situations filled with uncertainty.

The exhibit includes:

•Narrative medicine panels along with a collection of drawings of the late Lacie Wallace, created by Wheeling’s Independent Artist Group over an eight-year period and throughout her battle with colon cancer

•Photographs from internationally recognized photographer Angelo Merendino’s documentary “The Battle We Didn’t Choose – My Wife’s Fight With Breast Cancer”

•The Bodice Project – a collection of uplifting and sensitive torso sculptures

•Portraits by photographer and Flashes of Hope contributor Keith Berr

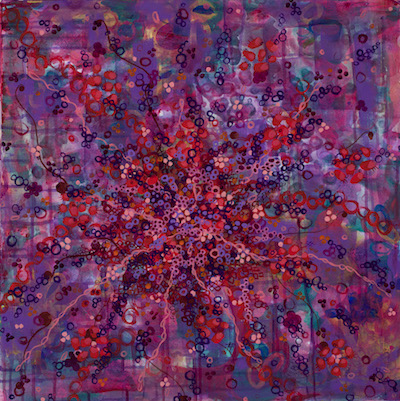

•Unique paintings of microscopically deconstructed cancer cells by Angela Canada Hopkins

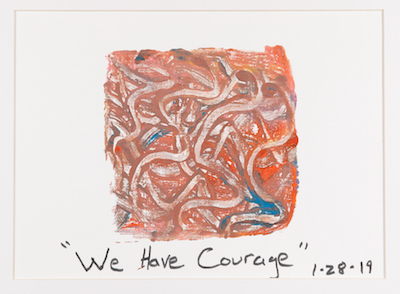

•Powerful and abstract paintings by Shawn Thornton, done while battling cancer of the pineal gland

•Arts in Medicine pieces done by patients at the Bing Cancer Center during therapy sessions