Blogger Connects with Faces in Gripping Portraits by Jay Stock

I’m going to preface this blog on photographer Jay Stock with a confession: I don’t understand art. It’s something I hide from friends and do my best to keep under wraps because a modern woman in her thirties who earned both a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Fine Arts should understand something about art. I’ve spent the better part of my life reading books, playing with cameras, and listening to NPR. That should cover my bases, right? But deep down, I’d be lying if I said I really enjoyed art. I can’t recognize it, or dissect it, and thus; I don’t think I appreciate it.

Consequently, when Oglebay Institute asked me to attend the opening reception for the new exhibit, “Just People,” by local photographer Jay Stock I groaned inwardly. How was I going to convey the importance of an exhibit if I didn’t know what I was seeing? Ultimately, I decided I’d show up at the Stifel Fine Arts Center and fake it.

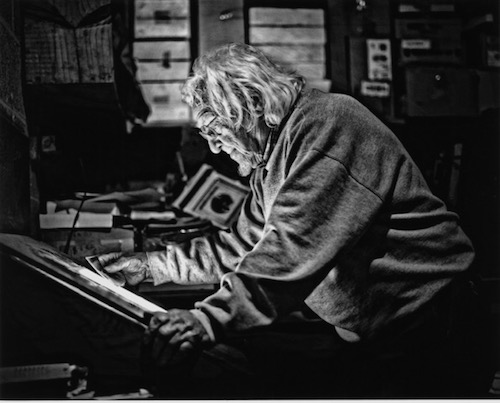

I read his bio before the show. Jay Stock turns 93 this month, and the term “local photographer” doesn’t do him justice, as his photography career spans 72 years. At age 18 he began to take photos while serving in the army, and he continued this pursuit after returning home, marrying, and going to work in the coal mines of Ohio. He attended The Progressive School of Photography in New Haven, Connecticut, and eventually opened a studio in Martins Ferry. And while that might have been a comfortable place for some people to land, Stock went on to become the first photographer to exhibit his work in the United States Capital Building in Washington, D.C. His “Faces of Today’s American Indian” was exhibited at the White House, and he has amassed more awards than any other photographer. Jay Stock is one of only a handful of living members of the Photographic Hall of Fame. He’s traveled the world capturing people on film, and now a collection of these photographs is hanging in the Stifel Fine Arts Center.

I slipped into the reception and followed the crowd as they trickled past the images on the wall. As the title of the show promised, the black and white photographs depict people. They sit, they stand, they work, they hold signs and babies. I recognized Doc and Chickie Williams, but Stock’s subjects were strangers, mostly: Native Americans, Amish, coal miners, a nun. As I watched visitors quietly stare into all of the framed faces I began to realize that there was nothing expected of me here. Nobody was waiting at the end of the exhibit with a clipboard and a series of probing questions. My job, as a viewer, as the person experiencing Jay Stock’s photography, was to look and to feel. And so I let my guard down and pocketed my notebook. By the time I made my way to the second floor, I was really looking into these faces, and I began to feel an inkling of a connection.

I was lucky to have a chance to talk with Stock’s daughter, Georgette Stock, about her father’s long career, but she told me that her dad “wasn’t born with the gift of photography; he worked at it.” I find that difficult to believe, but she shares memories of his early days establishing himself here in the Ohio Valley. “Years ago, when my mother and he were starting their business…mom would look in the paper and find out the engagement announcements.” Then they’d shoot the wedding. She told me that she still meets people who fondly remember her father taking their wedding photos.

When I asked her about “Just People,” Georgette told me, “It’s really a retrospective of his passion for the world. He loves people, he loves diversity.” But she also assured me that while her father’s name is on the exhibit, his career in photography was very much a product of his lifelong partnership with his wife, Georgette’s mother, Julia Mae Stock.

“She was so much a part of everything,” Georgette told me, recalling how Jay and Julia built their first darkroom in Julia’s parents’ kitchen, and how Julia would iron the brides’ dresses. “She was just a really remarkable lady. They were a team; they did it together.”

When you visit “Just People,” you’ll no doubt connect with some of Stock’s subjects, but I can’t tell you which ones will strike you. Though I’ve spent time in the beautiful desert southwest, the photographs that most struck me were those of West Virginia, of a time and a place right here and yet long gone. I don’t come from a mining family, so the image of two men about to descend into a mine, titled “Working in Hell,” felt personally foreign but still gave me a strong sense of place and struck an indelible West Virginia-chord. Nearby, a photo titled “The Coal Miner’s Daughter” showed a sooty-faced miner proudly holding up his infant girl. Beneath his hands, black with coal dust, the caption read: “To be loved as to love brings happiness.”

Brad Johnson, director of art education at Oglebay Institute, considered Stock a few years ago during a 2012 Stifel exhibit, explaining Stock’s innate ability to reveal more than just the faces of his subjects. “Jay can go anywhere and work with any group, even groups that typically don’t like to be photographed,” Johnson said. “He becomes personally involved with his subjects. People just get a sense of comfort with Jay. As a result, he captures images that most could never get. That personal connection is always apparent in his photographs.”

I went back to see the exhibit a week later when the busyness of the reception had evaporated and the photos hung silently on the walls. I’d been continuously caring for my son, who’d just had his tonsils removed, and watching the tragedy unfold in Orlando. I was drawn to a photo of two people holding hands as they walked down a road, about to disappear into a blanket of fog. Titled “Mother and Son,” the caption read: “Feeling that warm clasp and seeing the bright eyes that look at you with trust compels us to pledge that whatever wisdom and strength we have will be given making a pathway cleared of the stumbling blocks of hate, war, bigotry and selfishness.” It was as though that photograph appeared at a moment when I would truly understand it. As Georgette reminded me a few days later, “The arts transport you beyond where you are. The arts bring hope. The arts bring life.”

I probably still don’t appreciate the subtle nuances of each piece or admire the lighting in this photo or the shadows in that one. But I connected with the mother in that photograph. I felt, for a moment, what she felt, and understood why I was looking at her. The time and space between my world and hers dwindled, for a second, until whatever separated us dissipated entirely.

Jay Stock’s “Just People” will be shown at Oglebay Institute’s Stifel Fine Arts Center through August 12. Even if you don’t think you understand art, I’d urge you to meet the people in Stock’s photographs. They have things to say.

– Laura Jackson Roberts, author

(For more information, please call the Oglebay Institute’s Stifel Fine Arts Center at 304-242-7700 or visit www.oionline.com . “Just People” can be viewed free of charge Monday – Friday 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturdays 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.)