By Phyllis Sigal

Like teen sleuth Nancy Drew, Kara Yenkevich cobbled together bits and pieces of the life of Jeanie Caldwell Dougherty to create an impressive exhibit of the Wheeling native’s paintings.

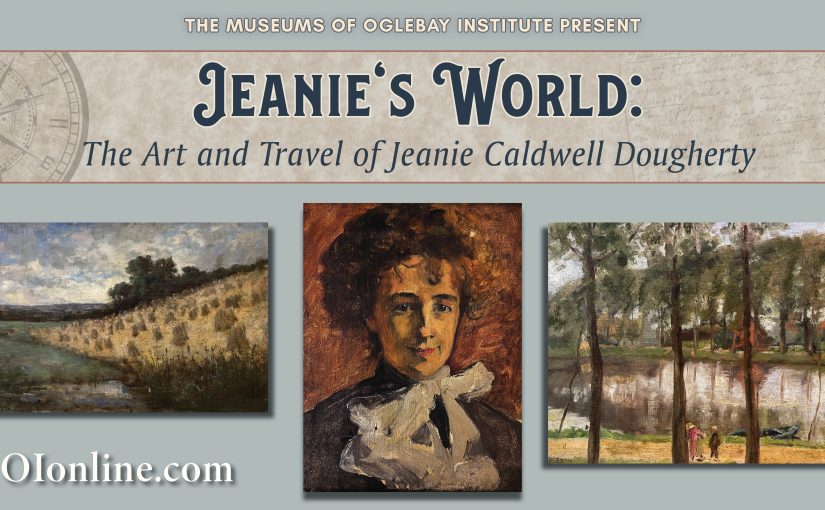

“Jeanie’s World: The Art and Travel of Jeanie Caldwell Dougherty,” on display at Oglebay Institute’s Mansion Museum, explores the life of a talented, independent female artist.

Through postcards, a diary, newspaper clippings, conversations with Jeanie’s great niece, and the artwork itself, Yenkevich curated a fascinating glimpse into Jeanie’s world.

Still missing, though, are many facts about the prolific artist’s life, as well as a number of her works of art. “I wish she would’ve helped me out and dated her paintings more. Maybe she wanted it to be a mystery?” Kara joked.

WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT JEANIE

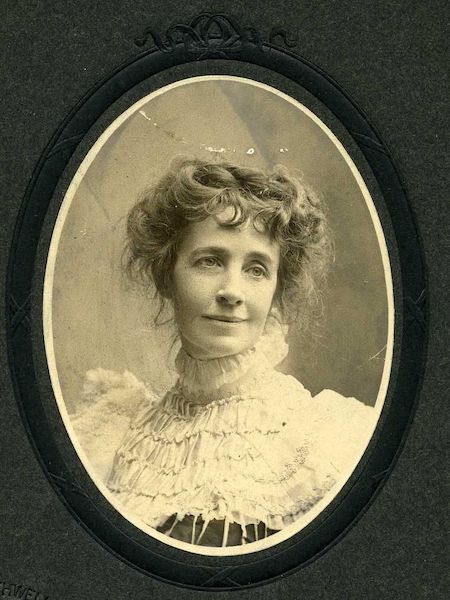

Jeanie (pronounced JENnie) left Wheeling at the age of 15 when her father was appointed the U.S. consul to the Hawaiian Islands by President Abraham Lincoln in the 1860s. She met her husband, Thomas Templeton Dougherty, who served as vice-consul to Hawaii under her father. The two married when Jeanie was 19, but his early death left her a widow at the age of 30.

At that time she embarked on her life of independence, travel, and painting.

The young widow “saw an opportunity and latched onto it, then hit the ground running,” Yenkevich said.

Kara admitted that she is a little jealous of Jeanie’s exotic and interesting life.

“I do think she was living this very unusual life for a woman of that time,” Kara noted.

As a widow with means, she lived this life she desired.

Jeanie never remarried and spent much of her life traveling with her sister, Eleanor. Eleanor, who remained single, also studied art but then shifted to writing at some point in her life.

NOT JUST A ‘SUNDAY PAINTER’

Jeanie was quite prolific and living as a “working artist” during her lifetime. With “serious aspirations,” she wanted to be more than a “Sunday painter.” Many women of the time took up painting merely as a hobby.

In the late 1870s after her husband’s death, she began to paint seriously. A classically trained artist, she studied in the areas of realism, pen and ink drawing, portraiture, nudes — all in the pursuit of being a well-rounded artist, Kara said.

She was also very interested in politics, “a citizen of the world … living a very global life, interested in what’s going on around her,” Kara discovered.

And, as a woman, she worked to find “the closest thing to equality that she could’ve,” Kara explained. She surrounded herself with people who valued her as an equal.

At several times in her life — in San Francisco and then in Italy — she studied under Frederick Yates, a well-known portrait artist who accepted both male and female students.

When she arrived in Paris, she approached Académie Julian — the only academy to admit women as well as international artists. She also submitted works to the Paris Salon, the largest exhibition in France.

A talented portraitist, she focused on people and everyday life. She captured a Shakespearean actor, a Vatican guard, an organ grinder, a gondolier, showing her belief that “people are the best way to capture the culture and the setting of a place.”

DIGGING (IN) THE DIARY

Kara gives “many thanks” to Margaret Dakin, Jeanie’s great niece, who provided her with photos and postcards, as well as a copy of the treasured diary that spanned the years from 1886-91.

Serving as a travelogue of sorts, the diary detailed where she was living, what she was painting, and who she was meeting, “so we get a sense of her in her own words,” Kara said.

Jeanie writes about leaving San Francisco where she lived and worked for some time, going to New York — to see the Statue of Liberty that had been recently unveiled — before traveling to Italy. She then went from Rome to Paris, where she spent most of the time detailed in the diary.

TRAVELING AROUND THE WORLD

She also wrote about her travels during those five years — to Germany, The Netherlands, Belgium, London, and the French countryside. She wrote about the museums she visited. Jeanie called painter J.W.M. Turner (the forefather of Impressionism) a “revelation.” She talked about Monet, whose work she had mixed feelings about, calling him a bit “odd.” She admired American painters John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler — both of whom “she rhapsodized about in her diary,” Kara shared.

Westminster Abbey, one of the few famous locations she captured, was described in her diary. She shared information about the cast of characters she met; an elderly artist who wouldn’t tell where the other painters stored their paint; a police detective who noted her absence one day; and a host of tourists who passed through the building while she painted.

The diary documents her work on a particular painting of an organ grinder: a struggle with her concierge about allowing the man into her apartment; going to the Botanical Garden to get a monkey; painting a fountain at the Tuileries; adding a dog, taking the dog out; how she puts it all together; and finally, getting a frame for it. We get a “complete sense of her process,” thanks to the diary.

PAINTINGS COME HOME

In the mid-1940s, well-known Wheeling photographer George Kossuth bought the Caldwell family home in North Wheeling, where Jeanie’s father and brother lived when they returned to Wheeling after the father’s stint as U.S. Consul to Hawaii ended. (It ended in scandal, but that’s another story … one mentioned by Mark Twain in one of his travel journals of the day.)

He discovered some of Jeanie’s paintings in the home’s attic, and he turned the discovery into a newspaper event.

On July 9, 1944, the Wheeling News Register published this article:

“Unreal as a fairy tale come to life is the story behind the rare collection of Jeanie Caldwell Dougherty paintings, hidden for half a century in a Wheeling attic, [and] which will be shown at an exhibit at the Oglebay Park Mansion-Museum, opening Wednesday, July twelfth. But even more fantastic is the unusual story of their uncovering and restoration by George J. Kossuth, prominent Wheeling photographer, who has spent four years restoring forty-five of the original two hundred and is still working on the remainder.”

“[Kossuth] was maybe the first advocate of her work — that she was talented, and her works were worth preserving,” Kara noted.

The pieces in the attic — apparently 200 of her favorite paintings — had been sent home to her family for safekeeping. (With all the traveling she was doing, “what was she doing with those paintings?” Kara wondered.)

WHERE ARE THEY NOW

“This is just a small sampling,” Kara said of the prolific artist’s work, many pieces of which are missing.

In 1957, Kossuth presented 13 restored paintings to Bethany College. Oglebay Institute’s Mansion Museum also became a recipient of two of her paintings, while some were sold to the Four Seasons Galleries of Wheeling. In 1995, more than 50 years after the discovery of Jeanie’s paintings, Kossuth’s daughter, Mary Kossuth Shumate, donated 25 pencil sketches, and a palmbook containing 42 pages of field notes and sketches, and 37 paintings and drawings, to Bethany College.

In 2021, Bob and Amy Mead donated 31 of Jeanie’s paintings to the Mansion Museum. Bob Mead is related to Jeanie through her niece — the daughter of her brother, Alfred Caldwell, married into the Mead family.

A PERFECT MARRIAGE

Interestingly, the current exhibit reunites pairs of paintings. For example, Bethany owns one of a set of paintings of a baby — baby eating, baby sleeping — while the Mansion Museum owns the other.

The Mansion Museum houses the aforementioned painting of the organ grinder. A painting of just the organ grinder’s head resides in Bethany’s collection.

Kara expressed her gratitude to Bethany College for loaning Jeanie’s works for the exhibit, which Kara believes is the “biggest retrospective of her work ever.”

“I really want people to learn about her,” Kara said. While there are a lot of talented unknowns from Wheeling, “I think she’s the most prodigiously talented unknown in Wheeling,” Kara said.

Jeanie was “artist, traveler, observer, all at the same time, and her body of work shows that.”

DETAILS

View more than 50 works of art and Jeanie’s own words that detail her life in the Sauder Gallery at the Mansion Museum through Nov. 1. Visit online for viewing hours and more information .