TOWNGATE OPENS 2016-2017 SEASON WITH TENNESSEE WILLIAMS’ THE GLASS MENAGERIE

Some amazing American playwrights have written outstanding plays that stand the test of time. Many of these playwrights have made significant contributions not just to theater but also to culture and creative thought. Playwrights such as August Wilson, Arthur Miller, Wendy Wasserstein, Edward Albee, David Mamet have made us laugh and cry. We realize our humanity through their words.

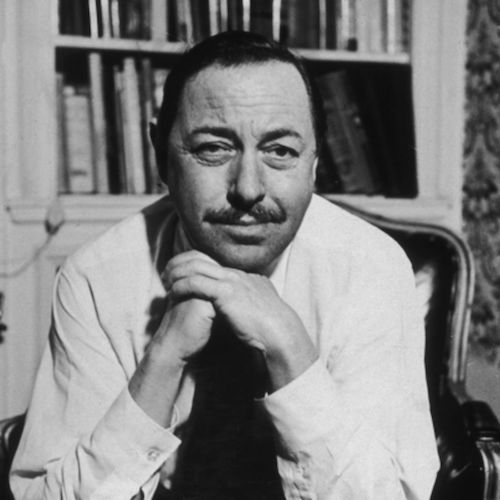

One of our greatest American playwrights was Tennessee Williams. He wrote many classic American plays such as A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and The Rose Tattoo.

Williams’ plays are predominantly set in the American South and feature characters who are emotionally or physically damaged in some manner. Often heart wrenching, always thought provoking, Williams’ plays speak to what it means to be human and the struggles we face in life.

TOWNGATE BRINGS TENNESSEE WILLIAMS TO YOU

Our community gets to experience Williams’ beautiful work. Towngate’s opening play of the 2016-2017 season is Williams’ The Glass Menagerie.

His first major success as a playwright, The Glass Menagerie tells the story of the Wingfield family. We meet frustrated artist Tom and his badgering mother, Amanda, who is often lost in her Southern Belle past. We also meet Tom’s agonizingly shy sister, Laura. The story follows the consequence a visit from a “gentleman caller” for Laura has on their lives. Partially based on Williams himself, and his own mother and sister, the characters show the difficulty they have in accepting and relating to reality. Each member of the Wingfield family is unable to overcome this struggle. As a result, each withdraws into a private world of illusion, finding comfort and meaning that the real world does not seem to offer.

The Cast is Superb.

Dave Henderson directs the Towngate production. A remarkable cast of local actors is currently rehearsing for what is certain to be a tremendous production.

Cathie Spencer plays Amanda, a proud and overbearing mother. Jamie Stout plays Laura, Amanda’s excruciatingly shy daughter who has withdrawn from the outside world. Brendan Sheehan stars as Tom, Amanda’s son and Laura’s younger brother who supports the family but wishes he could escape his life. And Michael Wylie plays the role of Jim O’Connor, an old friend of Tom and Laura who is brought to the Wingfield home in hopes that he and Laura will become involved romantically.

The performance runs September 16-18 and 23-24. Tickets are on sale now. Purchase in advance at OIonline.com or by calling 304-242-7700. You can buy tickets at the door, too. Admission is $12.50/$11 OI members.